by Dr. Louis Markos

I’ve never doubted that C. S. Lewis, were he alive today, would be a great fan and supporter of classical Christian education. But what aspects of this vibrant and growing movement would have garnered his particular praise? Though I can’t “prove” my response to this speculative question, I do think that, based on Lewis’s published works, I can make a firm educated guess as to which aspects would have complemented his own vision of goodness, truth, and beauty.

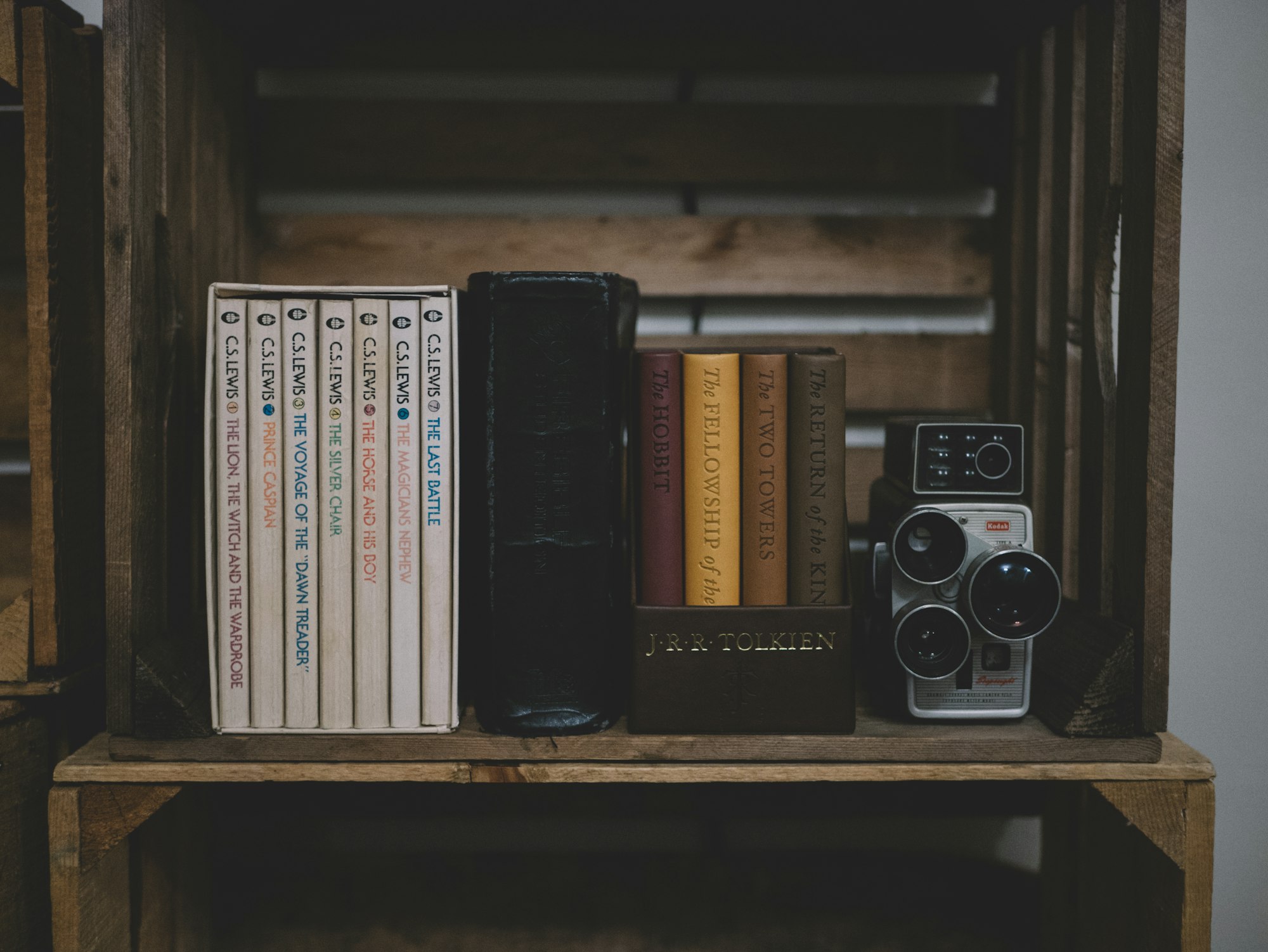

The author of The Chronicles of Narnia could not have helped but been enthused by the way classical Christian education refuses to dumb down its curriculum or speak “baby talk” to its young charges. Lewis knew that young people were capable of greater wisdom, joy, and virtue than we give them credit for, and that they love nothing more than an honest challenge that treats them as moral agents with an innate desire to understand and to grow.

The Chronicles are filled with one-on-one dialogues between Aslan and a child who has made a selfish, sinful decision that has brought bad consequences to himself and everyone around him. The best example of this is when Digory, in The Magician’s Nephew, allows his prideful curiosity to push him toward waking up an evil witch who almost destroys London and then brings evil and corruption to Narnia on the very day of its birth. Though Aslan eventually forgives Digory and allows him to carry out a difficult task that helps protect Narnia from the witch, he does not do so until he forces Digory, through a slow, grueling series of questions, to recognize the exact nature of his sin and how he could have prevented falling into that sin in the first place.

Lewis would have appreciated the way classical Christian school and homeschool educators hold their students to a high standard of ethical behavior, making sure that they not only act well but also know why they are acting well. Virtue is not a thing to be memorized, but a thing to be instilled, written deep in the heart and soul of the child. To understand both the nature of the choice and the consequences that flow from it is a concern that classical Christian educators have with the creator of Narnia.

But that does not mean that either Lewis or the practitioners of classical Christian education believe that learning must ever be a stern and didactic affair. Far from it! Joy, pleasure, and play run rampant in Narnia; there is a proper time for rejoicing, just as there is a proper time for mourning. Few Christian writers would have included that wonderful scene between Aslan, Susan, and Lucy that takes place just after Aslan has risen from the dead (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe). Rather than attend a church service and sing hymns, the three throw themselves into a wild romp as the Risen Lion and the two girls roll together on the grass until they are exhausted.

Classical Christian education is a serious business, as Lewis would want it to be, but it does not shy away from laughter, dramatic participation, and contagious creativity. Facts must be learned and foundations laid, but all is drenched with story and myth and the adventure of human history. The journey through the trivium, like that through Narnia, is full of twists and turns and surprises. One never knows what might be waiting around the next bend. One might find the classical virtue of courage in the most unlikely of places: in a chivalrous talking mouse named Reepicheep (Prince Caspian) or a perpetually pessimistic and gloomy Marshwiggle named Puddleglum (The Silver Chair). Or in a precocious but shy fifth grader learning about the Crusades or memorizing Latin verbs or kicking the winning soccer goal.

And something else. Behind the learning and the fun, a sense of awe in the presence of what Lewis called the numinous. When the children meet Aslan in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, they discover, for the first time, that something can be beautiful and terrible at the same time. This theme is repeated again and again throughout the Chronicles. Aslan is good, but he is not safe, loving but not tame. He can be embraced but he is never to be trifled with.

When Eustace-turned-into-a-dragon meets Aslan in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, he is afraid: not physically afraid, for a dragon is much stronger than a lion, but morally-spiritually-emotionally terrified, for he has never met anyone with such power, authority, and presence. He feels fear, but it is a qualitatively different kind of fear than one feels when one’s life is in danger. He is not afraid of what Aslan might do to him; he is just afraid of Aslan himself.

Lewis would surely have been thrilled by the emphasis that classical Christian educators put on teaching their students to feel reverence and awe before God’s holiness. Not the kind of reverence and awe that crushes you, but the kind that makes you hold your breath and feel the hairs on your neck stiffen. Classical Christian educators share Lewis’s high goal of restoring to our modern world a sense of the sacred, of the sacramental. Both want children who read the Chronicles to not only study the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, but also to feel it along their veins.

It is about more than learning; it is about having an encounter with the numinous Presence that thundered on the top of Mount Sinai, that caused Isaiah to cry out that he was a man of unclean lips from a people of unclean lips, that dwells in the midst of cherubim and seraphim that praise His holiness day and night without ceasing.

Shasta meets that Presence in The Horse and His Boy, and it nearly overwhelms him. And yet, out of the terror comes self-awareness, the consummation of all that has happened to him in his life. Classical Christian educators may not be able to bring their students before the Great Lion, but they foster in them the breadth of soul that would desire such an encounter and be able to survive it. And for that, Lewis would be most grateful. For opening the eyes of young people to the numinous is part of that noble battle for the souls of the next generation that we must win if we are to survive.

Oh, and one last thing. Lewis’s Professor Kirke would himself have been most grateful to classical Christian educators for teaching two things that the public schools have long abandoned: Aristotelian logic and, well, let the Professor say it himself in the last words he speaks in The Last Battle: “It’s all in Plato, all in Plato: bless me, what do they teach them at these schools!”

To be continued…

Be the first to comment